How do you conceptualize the multitude of possibilities in single session therapy? For this I turn to the rhizome. I have always experienced single session conversations as having a certain excitement and sense of adventure. So often the most enlivening aspects of the conversations related to unforeseen detours into sometimes moving and sometimes humorous story lines that seemed to invite ‘living talk’ and move away from what Tom Andersen (see Malinen, Cooper, Thomas, 2011) or my Finnish friend Tapio Malinen would describe as frozen talk- that kind of talk that keeps people stuck in static ways of knowing themselves.

However in the past few years this strange word ‘rhizome’ has been used increasingly in our therapeutic practice circles. Lynn Hoffman provides an intriguing account about how she has taken it up in her thinking. Walther and Carey 2009 make the direct relation of the rhizome to narrative practice. Laura Béres in Duvall and Béres 2011 reference the rhizome in discussion of the circulation of language as a reminder of the multiple meanings possible in a word and the complexity of language in therapeutic conversations. Fellow Canadian Vikki Reynolds takes up the image describing the messiness, overlapping imperfect guiding intentions and ethical stance in justice-doing (Reynolds, V. 2010, Reynolds & Polanco 2012). Still others broaden the image further re-conceptualizing how we organize knowledge and the interrelations throughout the world, brain science, and political movements. (See The Power of Networks).

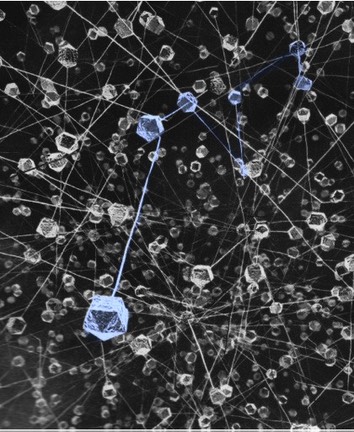

Rhizome photo from Ode Magazine

So what exactly is a rhizome? Many of you gardeners will be familiar with it’s structure. Bamboo has a rhizomatic structure as well as strawberry plants and many of those pesky weeds that you try to pull up when next thing you know you’ve traveled meters across your lawn following long filament roots that seem not to have a beginning or end. But more formally the understanding of the rhizome that has so many interested is best shared by French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in their book A Thousand Plateaus (1987).

Relating to the plant world, they propose a rhizomatic understanding of thought that highlights multiple, non-hierarchical off-shoots and entry and exit points in interpretation. The Rhizome is characterized as non-linear moving away from hierarchical linkages towards multiplicities that are linked or connected. Contrasting it to the common arborescent or tree like structures representing hierarchy and linear linkages the rhizome has no beginning or end but rather ever connecting offshoots to other appendages.

For our sake- the single session or brief narrative therapist- the concept of the rhizome highlights the multitude of possible entry points in stories that lead to many possible links and associations that when followed can be brought into themes or alternate stories supporting possibility and proposals for action. In this way the rhizome metaphor helps us think about the storying of life and the multitude of experiences that don’t get storied that have been pruned away yet lay out-there, loosely linked and waiting for rescue. “In relation to therapeutic practice we can consider how lines of rhizomatic inquiry can initiate off-shoots of stories which can then take root and develop as distinct but linked accounts of preferred story” (Walther & Carey, 2010, p. 6). This is a metaphor that invites us to re-think enquiry and what might be possible when we get outside the fields tradition of arborescent conceptualization of therapeutic conversations. It certainly is an image that expands what we are listening for in brief narrative conversations.

In an attempt to link this to practice I offer a simplified sample of enquiry.

In responding to a mothers utterance “I didn’t want to be here, I wanted to die” in arboristic style, one’s response may be narrow and tied to the past “wanting to die”. A binary understanding about wanting to die and not wanting to die may guide enquiry. Responses may include eliciting greater information about wanting to die, what the cause or precipitators were, and then conversation about preventing this expression in the future. Although this response may be useful to some people in some circumstances there is a great deal that is left out. The theme or plotline of the conversation remains as part of the problem saturated storyline.

Example of an off-shoot.

A rhizomatic metaphor renders responses tied to “wanting to die” as one of a multitude of possibilities. Responses informed by rhizomatic thought assist us to offshoot from the topic to alternate expressions perhaps implied but not explicitly stated yet related to the original utterance. Given this utterance is in the past tense it is implicit that she is wanting to live. Our enquiry could begin asking about how she was able to resist that 'want' at it's worst. Her response could implicate a certain kind of thinking about her daughter and the experience of her love in a very difficult moment in time. Exploring this further we offshoot to learning about the daughter and how the mother knows herself through her love. A response, “I’m knowing I am worth something” leads to enquiry about what that knowing helps her to do to which she may respond “to get help, to go to my doctor, to take better care of myself”.

After learning the details of ‘taking better care of myself’ a further offshoot still related to her well-being and safety but also to what she is knowing about her ‘worth’ and the actions that ‘sense of worth’ made possible could be, “What would you call those aspects –getting help, taking better care of yourself- are they like steps you are taking?” The response “Yes I guess they are” may then elicit our enquiry about what kind of steps they may be, which helps us to learn that they are “steps for self care”. Bringing forward the links in this way begins the piecing together of a theme, essential for the storying process. A story is in the making- a story of self-care informed by a sense of worth. Even further, leaving the more recent time-line to more distant time we may learn about other ‘steps for self- care’ the person has taken in the face of distressing events and very difficult circumstances. Where these events were previously unnoticed, through enquiry they are continually drawn into an emerging counterplot of self-worth and self-care. Other off-shoots may elicit a response to the question, "When you are taking these steps what do you suppose your daughter is learning about life, dealing with hard times, and mothering from you"? Are those aspects that you had wanted to pass on to your daughter? Is that close to the kind of mother you had always hoped to be? What is it like knowing she is learning these important life lessons from you? The speculations and experiences composing this plot-line are a distance from the experience of ‘wanting to die’ yet are still linked non-hierarchically. On an even further marginal offshoot, enquiry could leap into a future timeline inviting greater speculation about what this emerging plot will make possible for the person and their relationships in the near and distant future. Those speculations may then link back to long held wishes for life, values and motherly commitments once voiced.

In Curiosity,

Scot

References:

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated Brian Massumi, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Duvall, J., Beres, L. 2011. Innovations In Narrative Therapy: Connecting practice, training, and research. W.W. Norton, New York.

Reynolds, V. (2010). Doing Justice as a Path to Sustainability in Community Work. http://www.taosinstitute.net/Websites/taos/Images/PhDProgramsCompletedDissertations/ReynoldsPhDDissertationFeb2210.pdf

Reynolds, V. & Polanco, M. (2012). An ethical stance for justice-doing in community work and therapy. Journal of Systemic Therapies. 31(4) 18-33.

Walther, S. & Carey, M. (2009) Narrative Therapy, difference and possibility: inviting new becomings. Context, Oct.